|

Entertainment Magazine: Tucson: History Tucson's other early mission- Mission Santa Catalina de CuitakbaguJesuit priest faced off the ApachesThis is an excerpt from the complete book on the legends and history of the Santa Catalinas called Treasures of the Santa Catalina Mountains, by Robert Zucker and Flint Carter. Read more chapters about the lost legends of the Catalinas and download a free PDF sample of the book. Somewhere near the Cañada del Oro, north of Tucson, Arizona, there was another early Jesuit mission called the “Mission of Santa Catalina.” The San Xavier del Bac, the first mission in the Tucson area, was founded as a Catholic mission by Father Eusebio Kino in 1692. Father Gottfried Bernard Middendorff became the first priest to live at the mission north of the San Xavier del Bac Mission, 25 miles away, starting in January 5, 1757, reported Rector Carlos de Rojas. He said that Middendorff was then "in the Tucson with two pueblos" as mission branches." (from Roxas Marzo 15 de 1757, Spanish Colonial Tucson, Henry Dobyns, University of Arizona, 1976): Espinosa at Bac also had two branches, Middendorff's would most likely have lain farther north at Oiaur and Santa Catalina Kuitoakbagum. Such a situation would account for another Jesuit's memory that Middendorff worked at Santa Catalina. Certainly Middendorff established the northernmost mission on this particular rim of Christendom. Middendorff attracted approximately 70 families to his new mission with gifts of dried meat.

German priests assigned earlier to this mission field were required to learn Northern Piman before receiving independent assignments. For whatever reasons, Middendorff did not spend a year at San Ignacio learning the language before launching his Tucson effort. Consequently, he had to attempt to communicate with his prospective converts through an interpreter. “I had at first to instruct” the natives through an interpreter, Middendorff himself admitted in reporting his relationship to them. Quite possibly Middendorff alone was surprised one night in May when what he reported as 500 heathen savages attacked his mission. The priest and his military escort fled to San Xavier del Bac Mission with some native Piman families. Thus ended Middendorff's abortive attempt at proselytizing in the Tucson area. Notwithstanding the brevity of Middendorff's effort, its impact upon the Tucson population should not be underestimated. The five-month mission brought the Tucson people into direct daily contact with Spanish soldiery as well as with a Jesuit missionary. It taught the local Northern Pimans to look to the missionary for food subsidies, as well as to make reciprocal gifts in good Northern Piman fashion. It placed daily Mass on public view and almost certainly brought a fuller perception of baptism, marriage and interment in physical form if not in ritual meaning. It also fostered factionalism by creating a group loyal to the missionary and a group oriented toward aboriginal values. This northern mission was called Santa Catalina de Cuitoakbagum (Kuitoakbagum) or cuitabagu. Cuitabagu means "well where people gather mesquite beans," according to Tucson: The Life and Times of An American City by C.L. Sonnichsen: Middendorff's parish, called Santa Catalina de Cuitabagu, had an interesting history. When Kino and Manje came through in the 1690s, Cuitabagu which means "well where people gather mesquite beans" was twenty-five miles downriver north of the valley settlement. Later it seems to have been pulled back to a location in the Cañada del Oro eight or ten miles north of Black Mountain and close to the Catalina foothills, thereby gaining its saint's name. By the time of Middendorff's arrival it had been moved again and was probably close to San Agustin de Oiaur since the Jesuits liked to locate their missions in major Indian communities. Middendorff only lasted four month at this mission. He complained that his arrangements did not include provisions for housing. The new priest and his ten soldier escorts had to improvise shelters for themselves and their equipment. According to Middendorff's report in "Tucson: The Life and Times of An American City," he did connect with the locals. He was "fond of my catechumens and they reciprocated by affection with gifts of birds' eggs and wild fruits." But our mutual contentment did not last long because in the following May [1757] we were attacked in the night by about five hundred savages and had to withdraw as best we could. I with my soldiers and various families fled to Mission San Xavier del Bac where we arrived at daybreak. Had Middendorff been able to hold out, the date of the founding of Tucson might have been pushed back eighteen years. When the new Pima revolt broke out in 1756, however, he was in its path and unable to build on his shaky foundations. The village of Santa Catalina de Cuitabagu, where he made his attempt, cannot now even be located. Middendorff arrived at the mission after the attack on Father Alonso Espinosa at San Xavier, by Jabanimo, the Gileño chief in early 1756. (from Bernardo Middendorf by Ginny Sphar, Tumacacori National Historical Park). On January 5, 1757, Father Middendorf, with ten soldiers for protection, went to Tucson to found a mission. With gifts of dried meat, he soon attracted some 70 families. He had neither house nor church and slept under the open sky until he was able to erect a brush hut. On a May night in 1757 his beginnings were viciously destroyed. About 500 gentile Indians swept down and ravaged the village. The Padre and his ten soldiers fled and made it to San Xavier by daybreak.

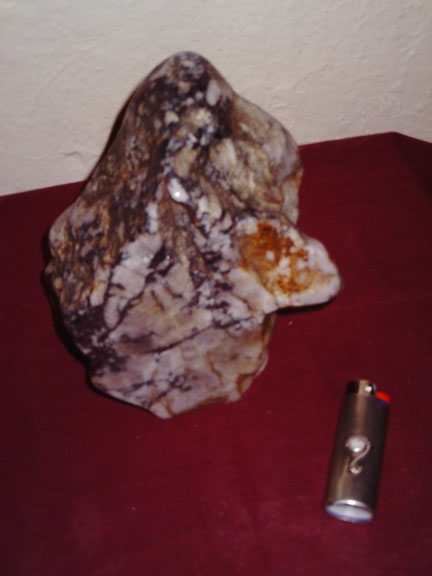

(from footnote: Dobyns, Pioneering Christians, p. 11. Dobyns maintains that this was indeed the cause, apparently following Pradeau, Expulsión, pp. 139-40, 178. Both of these authors suggest that Father Bernardo Middendorf shared the blame for provoking this attack. According to them, Middendorf founded a mission at Santa Catalina near Bac in September 1756. Actually, the innocent Middendorf did not set foot in the San Xavier-Santa Catalina-Tucson area until after the attack. He had only just arrived in the Pimería when he was named chaplain of the punitive expedition of November 1756. In December he apparently returned to San Ignacio where he waited with several companions for a permanent assignment. Sedelmayr to Balthasar, Mátape, December 6, 1756; quoted in Arthur D. Gardiner, “Letter of Father Middendorf, s.j., dated from Tucson, 3 March 1757,” The Kiva, Vol. XXII (1957), p. 1. At the base of this confusion seems to be a statement by Father Och: “Father Middendorf established a new mission among the Pápagos in Santa Catalina but the Indians were soon tired of it because they were barred from their vices, nightly dances and carousing. . . .” Treutlein, Travel Reports of Joseph Och, pp. 43-44. It was not until early in January 1757 that Middendorf went among the Indians of the Santa Catalina-Tucson area to found his ill-fated mission. This could be the first mission in the Tucson area, according to reports. The German Jesuit encountered the Northern Piman Indians living in the area “scattered in the brush and hills.” Personal Information on Bernardo Middendorfffrom National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior Born: 2/14/1723 in Westalia, Germany. Place and date of death unknown. Padre Middendorf professed his vows on October 21, 1741, arrived in the New World from Germany in company with Padres Gerstner, Pfefferkorn, Och, and Hlava in 1756. Assigned to a punitive expedition led by Governor Mendoza and Captain Elias Gonzales of Terrenate in November of 1756, after the attack on Padre Espinosa at San Xavier, he later returned to San Ignacio in December where he waited for a permanent assignment. On January 5, 1757 he was sent among the Indians at Santa Catalina-Tucson to found a mission. He had a ten-soldier escort. With gifts of dried meat he soon attracted some seventy families. However, on a May night his beginnings were destroyed by about 500 Indians who ravaged the village. He fled, arriving at San Xavier by daybreak. Father Middendorf stayed two weeks at Guevavi on his way to another unfortunate experience at Sáric, and Tucson reverted again to a visita of Bac. He baptized eight children while staying with Padre Pauer at Guevavi between August 6 and 21, 1757. By 1764 he was at Batuc completing the stone church that Padre Rapicani had started. He was arrested at Movas at the time of the expulsion, and eventually found his way into exile in his home country of Germany. The Lost Mission and the Iron Door MineThere is a legend of a lost mission in the Santa Catalina mountains that was destroyed by Apache Indians. An article from 1880 in the Arizona Weekly Star describes "gold mines were situated in these mountains and there was a place called Nueva Mia Ciudad, having a monster church with a number of golden bells that used to summon the laborers from the fields and mines, and a short distance from the the city which was situated on a plateau, was a mountain that had a mine of such fabulous richness that the miner used to cut the gold out with a 'hatchta.' At the time of the Franciscan acquiring thesupremacy the Jesuits fled, leaving the city desitute of population; before their flight they placed an iron door on the mine and secured it in such a manner that it would require a considerable time to fasten it." (from "Arizona Weekly Star, March 4, 1880) This was the legendary mine, the Mine with the Iron Door. It was also called the Lost Mission of Ciru in the city of the Valley Viejo. Read more about the Santa Catalina Mission. Mt. Lemmon jewelry grade silver ore in quartzFlint Carter, a Tucson, Arizona miner, has samples of "Cody Stone" mined in the Santa Catalina Mountains of Southern Arizona. This stone is jewelry grade silver and quartz ore, and weighs 8 pounds or more. It also contains scheelite and fluoresces. Valued at $5 a carat. This particular piece is the second largest specimen recovered. Extremely rare. There is a 40 page provenance of the object, including an assay by the University of Arizona and opinions from the Gem Institute of America and other sources. More samples of Cody Stone. "Ballads of the Santa Catalina Mountains" CDListen to songs and ballads on CD about the Iron Door Mine, the Santa Catalina Mountains, the Old West by Arizona historian Flint Carter. $9.95. Call 520-289-4566 for more information and to purchase directly. Mention the Iron Door web site. Tucson History | Treasures of the Santa Catalina Mountains | Iron Door MineTucson Entertainment Magazine© 2010-2017 EMOL.org. Entertainment Magazine. All rights reserved. |